Time As a Circle: Interpreting Arrival’s Use of Time, Language, and Memory

Everything within the structure of Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 film Arrival adheres to the perspective stated by its protagonist Louise in the film’s opening minutes. “...I'm not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings.” This statement, in turn, exemplifies certain guiding principles made by the filmmakers where certain filmic elements are concerned. While the film has a definitive beginning and end, within Arrival’s diegesis, the relationship between past, present, and future is uncertain until its concluding moments. The protagonist’s slippery relationship with time is reflected in the film’s presentation, where its dual narratives and flash- forwards contribute to a discussion on the nature of time and storytelling. Through the marriage of these nondiegetic elements to Louise’s perspective, Arrival explores the relationship between memory and language, and how our use of language influences our perception.

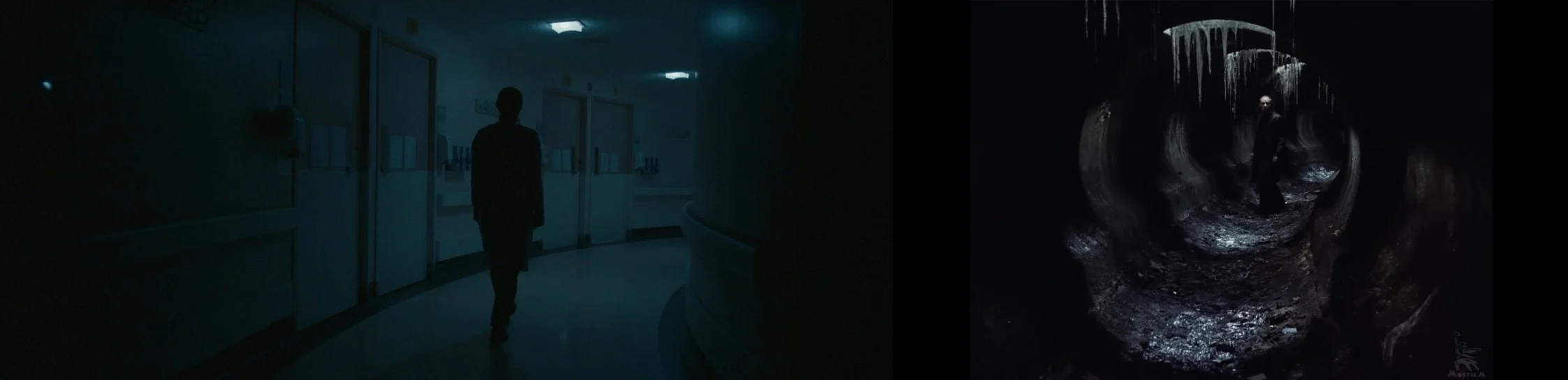

Villeneuve’s film Arrival (left) sometimes draws inspiration from Director Andrey Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker (right). In both works these tracking hallway shots under lights show the characters moving through liminal space. In the latter, the Stalker turns back to draw the Professor and the Writer onward on their journey from civilization to the heart of the mysterious Zone, a place that will grant their every desire. In the former, Louise travels down a hospital corridor. As with many sequences in the film it is difficult to place this in the character’s past, present, or future. This hall can be taken as a metaphor for time as it is depicted in the film: we can imagine ourselves moving through it, but the future is forever out of sight around the corner, while reflecting on the past grants us a broader perspective of our present (where Louise is relative to the viewer’s perspective, which trails after her).

Owing to Louise being the vehicle through which the viewer experiences both a linear narrative (the arrival of the heptapods and the world’s response to them) and a nonlinear narrative (the relationship between Louise and Hannah, her daughter), this analysis adheres largely to a linear perspective of time as its baseline, as defined by the film’s beginning and end. While Louise canonically has the luxury of experiencing time as having no definitive beginnings or endings, the remainder of the cast and the viewer do not. To begin a discussion of language and memory in Arrival, one must first establish the film’s relationship with time. Arrival’s approach to its two narratives is distinctive from other films. While the first narrative is expressed linearly (as most films are) and can be easily followed, Louise and Hannah’s more intimate story is nonlinear. This is not unusual: many films provide context through scenes of another time. Where Arrival stands apart is in its reliance on flash-forwards not only as an informative device but as an active contributor to the core narrative. Over the course of the film, Louise’s confusion over her visions dispels the notion that these events have already happened. She does not treat them as intrusive memories of past trauma, nor does it seem to occur to her that these could be visions of her future. This interpretation is further cemented by the question she asks regarding her visions when meeting Costello face-to-face (01:31:07). “I don’t understand. Who is this child?” Here, the viewer must bear in mind that though Louise is an active participant in these visions, her perspective of them is likely a first-person one, while their own is in the third. The broader perspective provides the viewer with additional information Louise cannot access: they see her with this child, can see the resemblance, and (being outside observers) understand faster than she that they are mother and daughter. One additional obstacle for Louise is the order in which she experiences these visions. Her experience of the future is (and remains) piecemeal and out of sequence, though it grows in clarity the more of the heptapod’s language she learns. As if to oppose the advantage a third-person perspective of events provides, the filmmakers hinder the viewer’s ability to interpret the latter narrative by never providing an orderly, cohesive montage that knits the various moments of Louise’s and Hannah’s life together. They are left to interpret the visions in the context of where they appear against the backdrop of the overarching linear narrative. Presumably, because these are Louise’s experiences, she is better able to untangle the order of events, as someone reflecting on their past can. Overall, temporality within the narrative is best considered in respect to whose time is under consideration: the protagonist’s, the ancillary characters’, or the viewer’s.

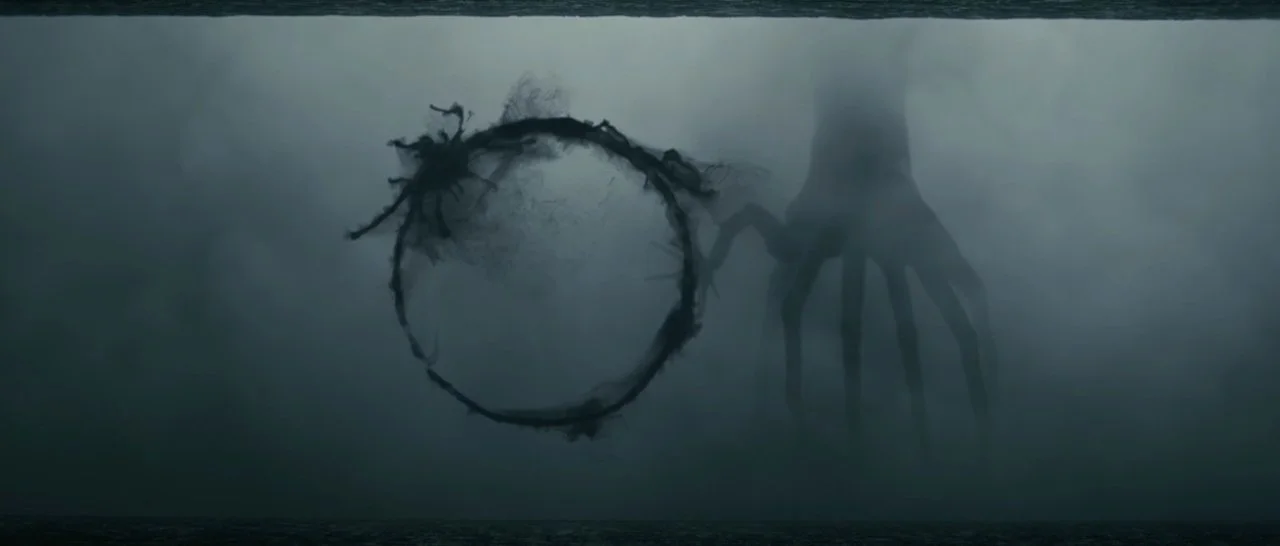

The heptapods demonstrate their semasiographic language.

Arrival images courtesy of Film-Grab. Please help support this important educational resource!

At various points throughout the film’s runtime, Louise’s active engagement with or reflection upon the heptapod’s written language (whether in their presence or not) acts as a trigger for her visions. Exposure to their spoken language does not, as evidenced by her exposure when first hearing their voices on a recording (12:05) and when first meeting them in person (30:47). Other instances of their spoken language are accompanied by visual elements, and the visions which follow those moments cannot be attributed to their spoken language. The distinction between the two can be attributed to their language being semasiographic, meaning their characters do not indicate spoken sounds as many human languages do. Within the film, Ian explains, “The first breakthrough was to discover that there's no correlation between what a heptapod says and what a heptapod writes. Unlike all human written languages, their writing is semasiographic. It conveys meaning. It doesn't represent sound” (53:58). Their language is also determined to be logographic. Logograms are characters that symbolize whole words or phrases. They are unlike pictograms, which visually portray what's being referred to, or phonograms, which represent sound. This leads Ian to postulate, “Like their ship or their bodies, their written language has no forward or backward direction. Linguists call this non-linear orthography, which raises the question, "Is this how they think?’” The question is references the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also referred to as linguistic relativity. In this hypothesis, language influences thought, in that the capacity of a language to describe something makes the speaker more perceptive toward things described in said language. One such example would be differences between two speakers as to how to describe a reddish cube with a blue tint. One speaker may, in their language, declare the object to be a red-blue rectangle. Another speaker in their own language may determine the object to be a magenta cube. Were the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis correct, the latter speaker could be regarded as being more perceptive to variations of color, as they have a specific word for the specific shade of red-blue on display, and can be reasonably assumed to have other words for other shades of red-blue. They could also be thought of as more perceptive where the object’s shape is concerned, as they can describe why a square is a rectangle, but a rectangle is not a square. Much of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has been debunked, though linguistic consultant for the film Jessica Coon, an Associate Professor at McGill and the Canada Research Chair in Syntax and Indigenous Languages, allowed in an interview that a language could have a drastic impact on human cognition if 1) it were sufficiently advanced and 2) it were not so advanced as to be incomprehensible to anyone seeking to learn it. Arrival conveys this complexity through the rapidity with which Abbott and Costello can convey whole concepts, their approach to writing (completing these concepts with no definitive beginning or end of the sentence), the altered perception of time the language grants those who become fluent in it. And though Louise heads a team of 50 highly-skilled linguists, interpreters, and mathematicians, that she alone is shown to comprehend the heptapod’s language to the point she can teach it is another indication of its complexity.

As Louise’s perception of past, present, and future changes, the heptapods reveal to her the immensity of their language, further fueling her shifting perspective.

One point of contention within the film from a casual observer may be the abrupt nature of Louise’s fluency with the language. Near the film’s climax, she and Ian are struggling to interpret an entire screen of logographs, which Ian laments could take years. All they can determine is the prevalence of the heptapod word for time among the logographs, and that what they’ve been provided is only 1 of 12 such sets. Several minutes later when Louise visits Abbott, the film provides subtitles for the language, implying that both onscreen speakers are fluent. Where did this sudden fluency emerge from? One interpretation could be that Louise never had to learn all of heptapod: she simply had to learn enough to remember a time when she was fluent enough to teach and write a book on the topic. This is corroborated by the many instances in which Louise pulls information from one moment of time to provide a solution to a problem in another (recalling from the film’s linear present the answer to a question from her future daughter, acquiring General Shang’s phone number and his wife’s dying words). Despite learning she is experiencing memories of the future, Louise still seems hardwired to regard her visions (now understood to be memories) as something that can only be drawn from the past. Following a vision of explaining why Hannah’s father left and doesn’t look at her the same way anymore (1:35:19), Louise says, “I just realized why my husband left me. My husband left me.” Ian responds, “You were married?” Ian still perceives time as linear, and because he does not share Louise’s altered perception and she has spoken in the past tense, he can only assume she is speaking of past events. Stephen Wolfram, Scientific and Engineering Consultant for the film, notes, “Our experience tends to be moment-by-moment. It's like this happens, then the next thing happens, then the next thing happens. And that's actually the way our language is set up as well: our language is very one-dimensional. You say one word, and then the next word, and then the next word. It doesn't have to be that way. Even when we look at things visually, we're confronted with a whole image all at once... Often, and in the way these things are analyzed in physics and mathematics, we're looking instead at, “What's the whole picture of what happens? Not step-by-step, but what's the whole thing that happens? What's the complete structure that gets built?” Rather than, "How do we set down every brick in the structure as we build it?” Distinctions between past, present, and future are integral to the English language: not only do we have words for these concepts, but there are rules as to how words must be altered relative to when they occurred. “I ran,” becomes, “I am running,” becomes, “I will run.” Our experience of time allows people to easily comprehend the first and second statements, but the last can only be a prediction until it occurs. It is variable whether someone will run. Here, Wolfram’s claim that our perception of language (and therefore memory, as one is used to convey another) does not need to be linear comes to the fore: treated like an equation, statements about the future (and the future itself) can become predictive with a high degree of accuracy. When the statement, “I will run,” is uttered by someone who does not allow themselves to become embroiled in the minutiae of running (having the proper clothes and shoes, checking the weather, planning a route, eating a light meal, grabbing a water bottle) and instead allows themselves a variable range of time in which they will run, running becomes inevitable. When and how are immaterial. This perspective largely explains why Louise still chooses to have Hannah, tell Ian about Hannah’s illness, and why she cries over a death she’s known for years was coming. That Louise is now able to experience the future as she does the past and the present does not alter her course because her memories of those events happening are as clear and distinct as memories of the past and her lived experience of the present.

Past? Present? Future? Does when an event occurs change its significance in our lives?

Arrival’s presentation enables serious discussion of the complex relationship between time, memory, and language. Outside of Louise’s interactions with the heptapods and other characters, the film’s muted tones can be mistaken as a reflection of her mind state, especially when considered alongside the film’s impactful opening of the life and death of her daughter. Yet the palette can also be interpreted as a statement as to the state of memories outside present experiences: they take on a muted quality, the details becoming hazy. The film’s score is similarly hazy: singular instruments are indistinct, outside the plaintive strings of the violin which bookends the film. Its presence during the most hurtful moments in Louise’s recollection reminds the viewer of the impact even dulled memories can have on us, provided they are the “right” memories. As Louise states in the beginning of the film, “... I'm not so sure I believe in beginnings or endings. There are days that define your story beyond your life.” Every vision of Hannah features one such defining moment: her birth, the first time her father holds her, time spent together, her diagnosis, her death. It cannot be coincidence that Louise is seen walking down a curved hospital corridor amid the opening montage, further establishing the film’s stance that time is a circle. Her perception of time becomes an invitation for the viewer to reflect on their use of language in the same way, to imagine the indistinct future to be as relevant as the present, and as powerfully emotive as the past.

Works Cited

Chiang, et al. “Principles of Time, Memory, & Language.” Arrival Blu-Ray, 2016.

Coon, et al. “The Linguistics of Arrival.” The Ling Space (2016), youtu.be/AkZzUWSiyn8.

Villeneuve, Denis. Arrival. Paramount Pictures, 2016.